Seventeen bombers lost in one night

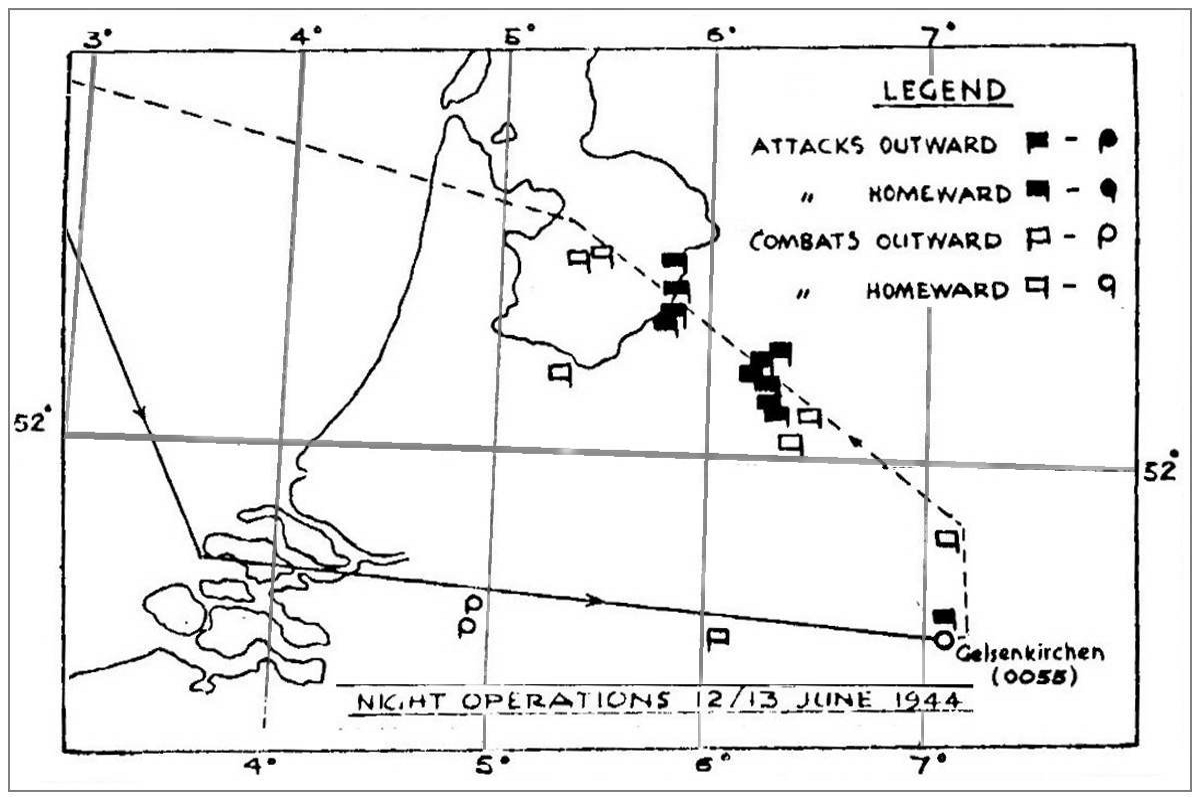

In June 1944, there was a feeling that the war would not last much longer. The Allied troops had landed in Normandy. June 6 was D-Day. A week later, in the night of June 12 to 13, 1944, the Oosteinde in Nunspeet was startled in the middle of the night by a crashing aircraft. It was an Avro Lancaster MK II bomber. Together with 285 other Lancaster bombers and 17 Mosquito fighter-bombers, they had destroyed the Nordstern Synthetic Oil Refineries in Gelsenkirchen (Gelsenberg AG) in the German Ruhr area that night, in such a way that the production of aircraft fuel for the Germans was disrupted for a long time. Seventeen English bombers were lost that night. One of them was the Lancaster MKII with registration DS818 and code JI-Q with the name ‘Maggie’ on one of the engine shields. The aircraft belonged to 514 Squadron and was stationed at Waterbeach, Cambridgeshire, England.

Lancaster 'Maggie'

Lancaster ‘Maggie’ was suddenly attacked by a German night fighter on the way back and had no chance. An explosion set the aircraft ablaze. Pilot Duncliffe later stated that he briefly lost consciousness. There was damage to the intercom system. Duncliffe gave the order to his crew to abandon the aircraft. Apparently not all crew members heard this. The aircraft lost altitude, flew on in the direction of Harderwijk for a while, but veered 180 degrees near the Bovenweg. The aircraft flew very close to the farm of the Polinder family at Oosteinderweg 112 and crashed at 01:32 in a nearby rye field on Oosteinderweg, next to the former poultry slaughterhouse, now . The wreckage was scattered everywhere. The tail section of the aircraft had already broken off earlier. The tail section and tail gunner Sgt. Keith Russell Baker (20 years old) came down in an oat field near the farm at Oosteinderweg 70 in the area where the Heemskerklaan was later constructed. Children found Baker’s body when they went to school in the morning.

Three survivors

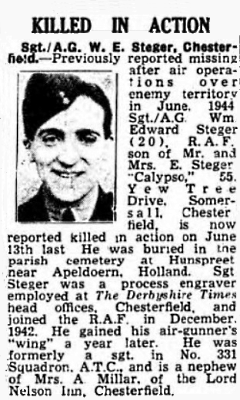

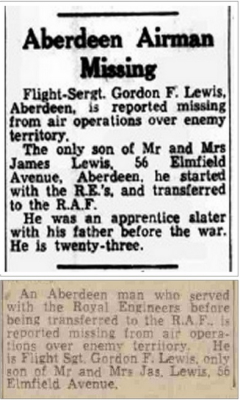

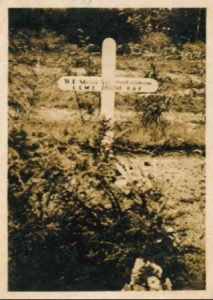

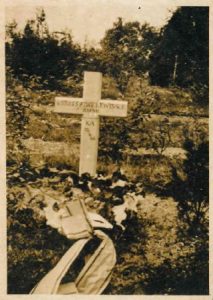

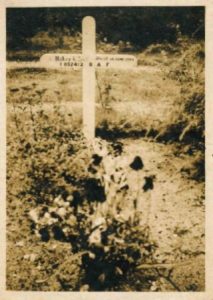

Three men were still in the burning plane. One was Sergeant William Edward Steger (20 years old), air gunner. The other two bodies were so burned that it was difficult to find out who they were exactly. Only after the war did this become clear. They were: Sergeant George Kennedy Birse Brown (31 years old), Flight Sergeant and Gordon Florence Lewis (23 years old) navigator. The specific watch as a navigator provided a solution. Pilot Officer Duncliffe (21 years old) managed to bring himself to safety with the parachute. Flight engineer Sergeant Peter Geoffrey Cooper (24 years old) landed with his parachute in a beech tree in the lane where the deer park is now. He had a broken leg and was taken to hospital by the Germans. Bomb aimer Flight Sergeant Harry James Bourne (26 years old) landed above Wesinge near Doornspijk. Completely distraught, he was taken in by local residents, but he wanted to return to his comrades in the plane. There he was captured by the Germans. The two prisoners eventually ended up in the POW camp Stalag VII Luft near Bankau in Silesia (now Poland) via Amsterdam. The Russians advanced from the east and in January 1945 all prisoners were forced to leave the camp. After a two-week walk through the bitter cold (The Long March) they reached the POW camp Stalag III near Luckenwalde south of Berlin on 8 February 1945. In May 1945 the Luckenwalde camp with approximately 20,000 POW soldiers was liberated and Cooper and Bourne eventually returned to England. Cooper stated after the war that he survived thanks to the help of the Red Cross. Bourne suffered from frostbite for the rest of his life. The four deceased crew members were buried in the cemetery in Nunspeet on 15 June.

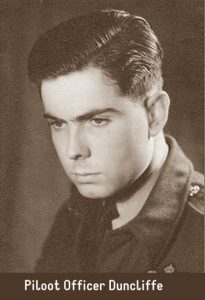

Derek Anthony Duncliffe

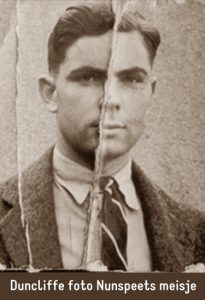

The police report from June 1944 states: “It is suspected that one of the pilots escaped by evading arrest by fleeing.” That suspicion was correct, because Maggie’s pilot, Pilot Officer Derek Anthony Duncliffe, had landed in the woods with his parachute. When resistance fighter Wim Mazier went to school in the morning, he came across a man in stocking feet. He thought for a moment that it was a German, but then saw from the uniform that it had to be an Englishman. Wim took him to an underground hut, got sandwiches and coffee at home and went back to the hut. The people in hiding there were surprised. They had never seen an English pilot before. Duncliffe then spent three weeks in the hiding camp “Het Verscholen Dorp” in Vierhouten. After that, Duncliffe was given various hiding places for the rest of the war in Nunspeet (Van der Schaar family, Harderwijkerweg), Doornspijk (Dr. Wolffensperger) and Apeldoorn (Mr. Kliest, Valkenberglaan). A girl from Nunspeet had a passport photo of Duncliffe. He was in Apeldoorn at the liberation and was able to return to England in April 1945. Duncliffe died in January 1996. He struggled with his war experiences for the rest of his life.

The police report from June 1944 states: “It is suspected that one of the pilots escaped by evading arrest by fleeing.” That suspicion was correct, because Maggie’s pilot, Pilot Officer Derek Anthony Duncliffe, had landed in the woods with his parachute. When resistance fighter Wim Mazier went to school in the morning, he came across a man in stocking feet. He thought for a moment that it was a German, but then saw from the uniform that it had to be an Englishman. Wim took him to an underground hut, got sandwiches and coffee at home and went back to the hut. The people in hiding there were surprised. They had never seen an English pilot before. Duncliffe then spent three weeks in the hiding camp “Het Verscholen Dorp” in Vierhouten. After that, Duncliffe was given various hiding places for the rest of the war in Nunspeet (Van der Schaar family, Harderwijkerweg), Doornspijk (Dr. Wolffensperger) and Apeldoorn (Mr. Kliest, Valkenberglaan). A girl from Nunspeet had a passport photo of Duncliffe. He was in Apeldoorn at the liberation and was able to return to England in April 1945. Duncliffe died in January 1996. He struggled with his war experiences for the rest of his life.

Impressive new monument

In 1994, the site at Oosteinde was searched for remains of the aircraft. Among other things, a propeller hub and a parachute clip were found. In December 2005, an investigation was conducted into the presence of conventional explosives. This was done on behalf of the Municipality of Nunspeet in connection with the construction of the De Kolk industrial estate. A detection investigation showed that there were ‘suspicious’ locations. 47 of these locations were investigated further. No explosives were found at any of these locations. The propeller hub has been incorporated into a beautiful new monument, erected at the roundabout near De Wiltsangh, in memory of this crash site.

Source: among others Elspeet Historie and Wessel Scheer